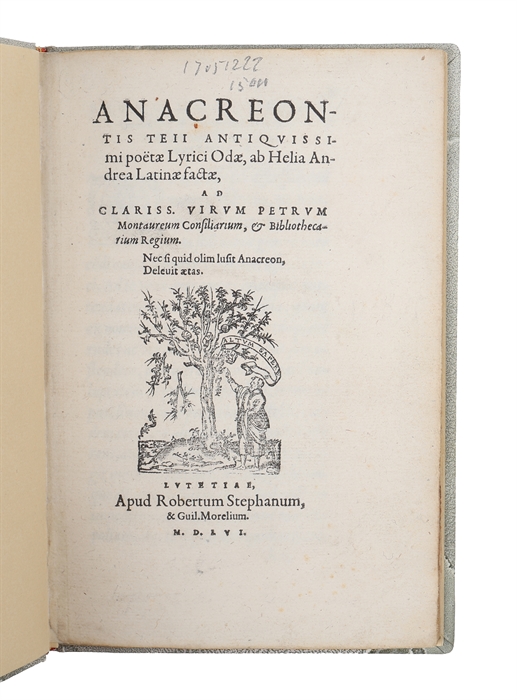

ANDRÉ'S SEMINAL LATIN TRANSLATION OF THE ANACREONTEA

ANACREON (& SAPPHO) - ANAKREONTOS.

Anacreontis teii antiquitissimi poëtae Lyrici Odae, ab Helia Andre Latinae factae.

Lutetiae (i.e. Paris), Robert Stephanum (i.e. Robert Estienne) & Guillaume Morel, 1556.

Small 8vo. Lovely newer full marbled paper binding with gilt leather title-label to spine (Jens E. Hansen, Aarhus). Light brownspotting to a few leaves and somne leaves towards the end with inkspotting at outer blank margin. Early neat handwritten marginal annotations throughout. A lovely copy. 54 pp.

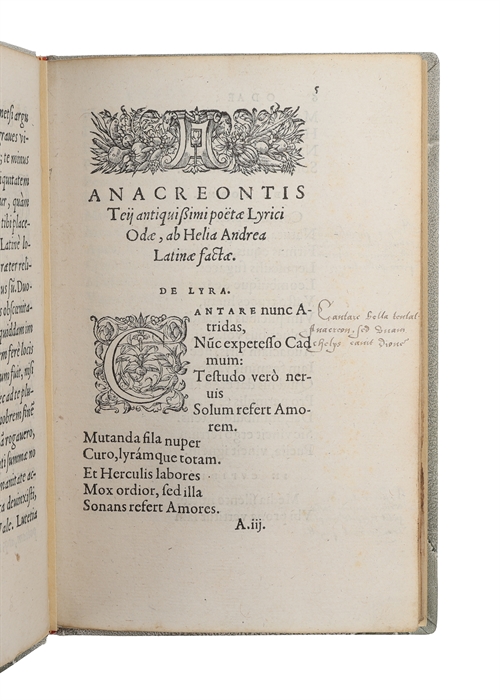

Scarce second edition of Elie André’s seminal Latin translation of the Anacreontea – the first complete - which itself is a classic in the history of classical literature. It came to directly influence all later readings of Anacreon. In 1554, Henri Estienne II published the seminal editio princeps of Anacreon, which is no less than an outright Renaissance sensation, causing the “Anacreaonta” to become the most influential “ancient” Greek poetic text during the Renaissance, initiating a poetic revolution in Europe. Simultaneously with this editio princeps, Henri Estienne published his own Latin translation of it, which constitutes the first translation into Latin. Merely a year later, in 1555, Elie André extremely important translation of the Anacreaontea appeared, in 1555, printed by Thomas Richard. This translation included additional Odes not in the Estienne edition and was thus the first complete Latin translation of the “Anacreontia”. The following year, 1556, Robert Estienne II published his first work, namely a second edition of the original Greek Anacreontea that Henri Estienne had published in 1554. Silmultaneously, Robert Estienne republished Elie André’s Latin translation, which was published separately, but which is often found together with the 1556 second edition of the Greek Anacreontea. “The first full translation of CA was again in Latin. It was published by the humanist Elie André (1509-1587) from Bordeaux, who was friendly with the Parisian circle around the Pléiade. André’s translation appeared less than a year after Estienne’s edition and comprised the Latin translation only, without the Greek text. In a way, this can be taken as a signal that the Latin tradition was coming into its own. Accordingly, André makes some bolder choices in his translation, which already shows in his first lines (see Aiijr): Cantare nunc Atridas, Nunc expetesso Cadmum: Testudo vero nervis Solum refert Amorem (…). In classical Latin, the verb expetessere is used only by Plautus (and it is extremely rare in postclassical Latin). This brings a somewhat odd ring of comedy to the poem. Here, and in a number of other places, the translator wishes to strike his readers with an unusual turn of phrase or by some sort of amplification. He does not just imitate ‘Anacreon’, but also competes with him (as arguably with Estienne’s translation). André’s willingness to adapt the original text shows also in a certain moralistic tendency not otherwise seen in Latin translations. On the one hand, he openly and avowedly changes the text when it comes to unequivocal references to homosexuality: in CA 12 (10).8-10 (τ? µευ καλ?ν ?νε?ρων […] ?φ?ρπασας Β?θυλλον; “Why from my sweet dreams […] have you snatched away Bathyllus?”), for instance, he replaces Bathyllus with a puella (Cur mane somnianti / Ista loquacitate / Mihi eripis puellam?),…; in CA 29 (17).1-2 (Γρ?φε µοι Β?θυλλον ο?τω / τ?ν ?τα?ρον ?ς διδ?σκω, “Paint for me thus Bathyllus, my lover, just as I instruct you”) he simply suppresses the word ?τα?ρον, “lover” (Mihi pinge sic Bathyllum / ... Estienne’s translation is: Meos Bathyllum amores, / Ut te docebo pinge). Here, André proceeds in a way similar to the original Neo-Latin Anacreontics, in which homosexual love simply does not occur. On the other hand, André makes generous use of a metatextual element which is less conspicuous than his changes, but is even more extensive and significant. He includes a considerable number of passages in quotation marks and thus identifies them as sort of sententiae. In CA 4 (32), for instance, lines 1-6 describe how the poet wishes to lie down on myrtles, drink, and have Eros as his wine steward. This description of a specific setting is followed by some more general lines about the brevity of life, which André includes in quotation marks (lines 7- 10): “Cita nanque currit aetas, / Rota ceu voluta currus. / Sed et ossibus solutis / Iaceam cinis necesse est” (“For hurried life runs along just like a rolling wheel, but I shall soon lie, a bit of dust from crumbling bones”). The focus of this quotation technique is on lines concerned with the transitory nature of life, the uncertainness of tomorrow, and the futility of riches. By marking out such lines as sententiae, André distinguishes Anacreon the philosopher from Anacreon the drinker and lover and contributes to a larger discourse about the morality of the poet and his poems. While opinions in antiquity were often critical of Anacreon’s morals, ‘Anacreon’s’ large flock of modern imitators was united to defend their hero’s virtue. From Estienne’s preface onwards they usually referred to Plato’s Phaedrus 235c, where Socrates calls Anacreon “wise” (σοφ?ς) in matters concerned with Eros. In the 18th century, Anacreon, the philosopher, could even turn into a key-image of enligthened discourses. André’s identification of sententiae in ‘Anacreon’ prepared for this development and could have had a direct influence on it since his translation was widely read until well into the 18th century. The Latin translations of Estienne and André soon became classics in themselves and were the most successful ones in the early modern period.” (Tilg: Neo-Latin Anacreontic Poetry. Its Shape(s) and Its Significance, 214. Pp. 177-78). Brunet: I:250; Renouard: I:(161).

Order-nr.: 62303