INAUGURATING THE SCEPTICAL REVOLUTION OF THE RENAISSANCE

SEXTUS EMPIRICUS.

Pyrrhoniarum hypotyposeon libri III, Quibus in tres philosophiae partes feuerissime inquiritur. Libri magno ingenii acumine, variaque doctrina referti: Graecè nunquam, Latinè nunc primum editi, Interprete Henrico Stephano.

(Geneva), Henricus Stephanus (Estienne), H. Fugger (typogr.) 1562.

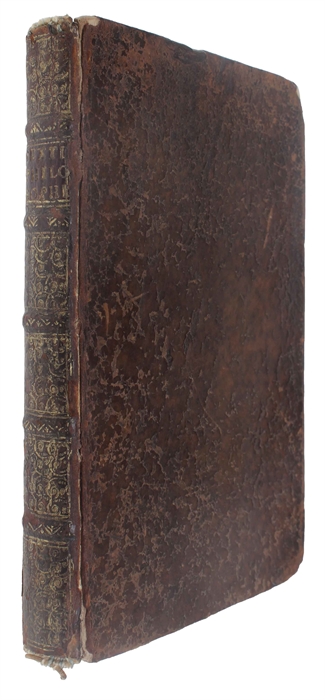

8vo. Near contemporary full calf with richly gilt spine. All edges of boards gilt. Wear to extremities and hinges, but overall tight and fine. Old owner's name to title-page and a stamp to blank margin ("Teres etque Rotundus")). A few early underlinings. Two leaves with a damp stain, otherwise unusually nice and clean. Title-page slightly soiled. Woodcut printer's device to title-page and woodcut initials. 288 pp.

The very rare hugely influential first edition of one of the single most important printings in the history of Western thought, namely the very first appearance in print of any of Sextus Empiricus' works, his great "Hypotyposes". This seminal printing inaugurated a new era in the history of Western thought. Together with the second edition of the work (by Hervet, 1569, with which the "Adversos Mathematicos" also appeared), the first appearance of Sextus Empiricus' work profoundly influenced the thought of Bruno, Montaigne, Descartes, as well as many other pivotal thinkers of the modern era, and caused Sextus to be viewed as "the father of modern philosophy".

"The printing of Sextus in the 1560s opened a new era in the history of scepticism, which had begun in the late fourth century BCE with the teachings of Pyrrho of Elis. [...] Before the Estienne and Hervet editions, Sextus seems to have had only two serious students, Gianfrancesco Pico at the turn of the century and Francesco Robortello about fifty years later." (Copenhaver & Schmitt, pp. 240-41).

Apart from being of seminal importance to the development of modern thought, the work is of the utmost scarcity and constitutes one of the rarest of all Estienne books.

"The first printed edition was by Henri Estienne (Stephanus) in 1562 of Sextus' "Hypotyposes". A second printed Latin edition of the "Hypotyposes" plus "Adversus Mathematicos" appeared in 1569. The text of the "Hypotyposes is that of Estienne, the translation of "Adversus Methematicos" was done by French counter-reformer and theologian, Gentian Hervet... The Greek text was not published until 1621 by the Chouet brothers." (Popkin, p. 18).

Having been almost completely neglected throughout the entire Middle Ages and the early Renaissance, the first printing of Sextus' work in 1562 is almost solely responsible for the inauguration of a new skeptical era that came to profoundly influence almost all thinking of the centuries to follow.

"As the only Greek Pyrrhonian sceptic whose works survived, he came to have a dramatic role in the formation of modern thought. The historical accident of the rediscovery of his works at precisely the moment when the skeptical problem of the criterion had been raised gave the ideas of Sextus a sudden and greater prominence than they had ever before or were ever to have again. Thus, Sextus, a recently discovered oddity, metamorphosed into "le divin Sexte", who, by the end of the seventeenth century, was regarded as the father of modern philosophy. Moreover, in the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the effect of his thoughts upon the problem of the criterion stimulated a quest for certainty that gave rise to the new rationalism of René Descartes and the "constructive skepticism" of Pierre Gassendi and Martin Mersenne." (Popkin, p. 18).

The discovery and dissemination of these foundational texts was nothing less than a epiphany. Scepticism was immediately absorbed into Renaissance thinking and quickly became a dominant strand of thought.

"The revival of ancient philosophy was particularly dramatic in the case of scepticism. This critical and anti-dogmatic way of thinking was quite important in Antiquity, but in the Middle Ages its influence faded [...] when the works of Sextus and Diogenes were recovered and read alongside texts as familiar as Cicero's "Academia", a new energy stirred in philosophy; by Montaigne's time, scepticism was powerful enough to become a major force in the Renaissance heritage prepared for Descartes and his successors." (Copenhaver & Schmitt, pp. 17-18).

"No discovery of the Renaissance remains livelier in modern philosophy than scepticism". (Copenhaver & Schmitt, p. 338). "The revived skepticism of Sextus Empiricus was the strongest single agent of disbelief". (ibid., p. 346).

Our knowledge of ancient scepticism comes almost solely from Sextus, who is introduced to the Renaissance in 1562 with this first printing of any of his works. From then on, skepticism grew rapidly, determining the course of much modern thought.

"Ancient Scepticism had a number of followers in the renaissance, especially in the sixteenth century, when the writings of Sextus became more widely known. [...] Scepticism in matters of religion is by no means incompatible with religious faith, as the example of Augustine may show; consequently this position had many more followers during the sixteenth century than is usually realized. The chief expression of this sceptical ethics is found in some of the essays of Montaigne, and in the writings of his pupil, Pierre Charon." (Kristeller, p. 36).

Adams: 1027.

See:

Kristeller: "Renaissance Thought II. Papers on Humanism and the Arts", 1965.

Popkin: "The History of Scepticism. From Savonarola to Bayle", 2003.

Copenhaver & Schmitt: "Renaissance Philosophy", 1992.

Order-nr.: 53121