NOBEL PRIZE IN MEDICINE 1934 - "ONE OF THE LANDMARKS IN THE HISTORY OF THERAPEUTICS"

MINOT, GEORGE R. (+) WILLIAM P. MURPHY.

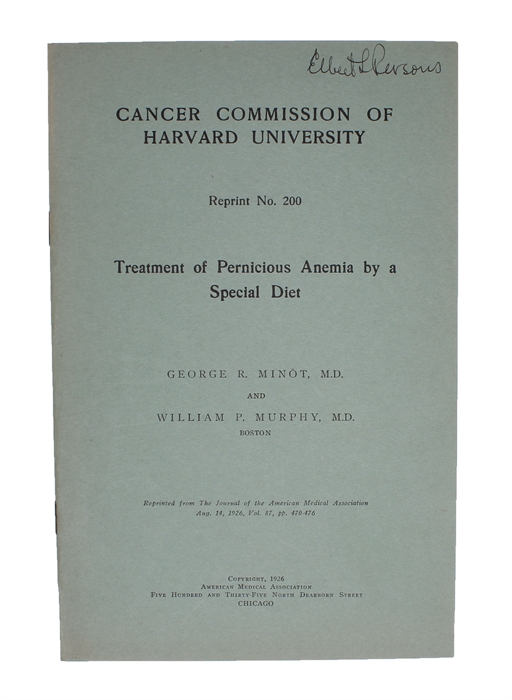

Treatment of Pernicious Anemia by a Special Diet. (Offprint from "The Journal of the American Medical Association", Aug. 14, 1926, Vol. 87, pp. 470-476).

Chicago, American Medical Association, 1926. 8vo. Offprint in the original printed wrappers. Previous owner's name to top right corner of front wrapper. A very fine and clean copy. 19 pp.

First printing, in the scarce offprint, of Minot and Murphy's seminal Nobel Prize winning paper which "ranks as one of the greatest modern advances in [anemia] therapy." (GM). Minot and Murphy shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1934 with George Whipple "for their discoveries concerning liver therapy in cases of anaemia". "The brilliant discovery by Minot and Murphy in 1926, demonstrating the dramatic effectiveness of liver preparations in pernicious anemia, forms one of the landmarks in the history of therapeutics." (Satoskar, Pharmacology and Pharmacotherapeutics).

"Prompted by pathologist George Whipple's research on the feeding of liver to anemic dogs, Minot and Murphy fed liver to their patients. In a now famous 1926 paper [the present], they announced its miraculous benefits for forty-five otherwise doomed souls." (Wailoo, Drawing Blood: technology and Disease Identity in Twentieth-Century America).

Up until the 1920'ies, pernicious anemia (also known as "blood thinning" disease) was a fatal disease, for which there was no cure. People who developed pernicious anemia - characterized by dangerously low counts of red blood cells - were left exhausted, hospitalized, and without the hope of being cured.

"Minot’s work and that of numerous pupils during the decade after 1926 initiated a new era in clinical hematology by replacing the largely morphologic studies of the blood and of the blood-forming and blood-destroying organs with dynamic measurements of their functions." (DSB).

In the early 1920s, most doctors believed that pernicious anemia was caused by a toxic substance in the body, and they prescribed doses of arsenic, transfusions, or removal of the spleen as treatments. But after these remedies were administered, patients had relapses, and death was inevitable. Across the world, 6,000 lives a year were lost to the scourge of pernicious anemia.

"In 1923, Minot met William P. Murphy, who had graduated from Harvard Medical School in 1922 and who was to become an assistant instructor at Harvard Medical School in 1924. In their investigations to find a cure for pernicious anemia, Minot believed that research by George Whipple, a researcher whom he had known while both were at Johns Hopkins Hospital, was particularly significant. Whipple had completed experiments in which he bled dogs to make them anemic. Then he determined which foods restored their red blood cells. His results showed that red meat and certain vegetables were effective treatments, but liver was the best treatment. Minot wondered if Whipple's findings with dogs could be duplicated in humans. He and Murphy were determined to try it, and proceeded to do so with their private patients. Observing an increase in the patients' red blood cell counts, they thought they were on the right track, and decided to try the experiment with hospitalized patients which eventually led to their landmark discovery." (The Harward University Gazette, 1998).

After Minot and Murphy's verification of Whipple's results in 1926, pernicious anemia victims ate or drank at least one-half pound of raw liver, or drank raw liver juice, every day. This continued for several years, until a concentrate of liver juice became available.

The active ingredient in liver remained unknown until 1948, when it was isolated by chemists Karl A. Folkers.

Garrison & Morton: 3140

Order-nr.: 51659