APHASIA FIRST DESCRIBED

LINNAEUS, C. (CARL v. LINNÉ).

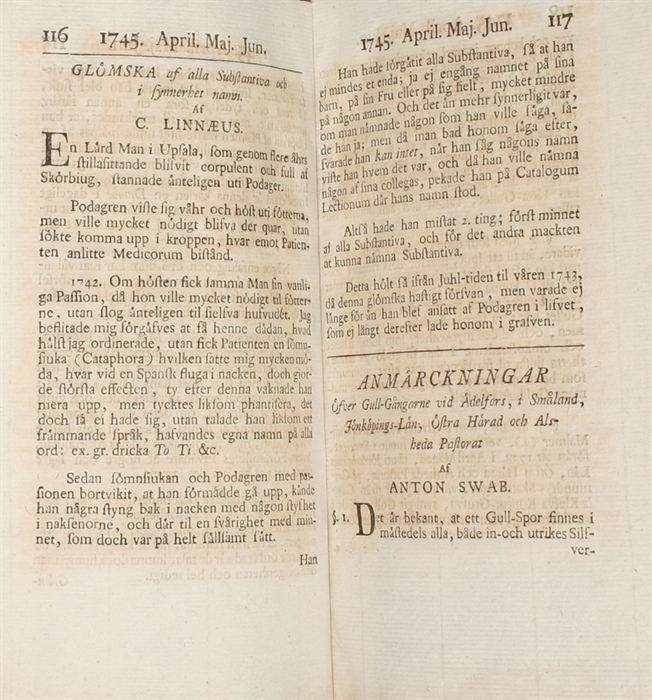

Glömska af alla Substantiva och i synnerhet namn.

[Stockholm], 1745. 8vo. Extracted from "Kgl. Svenska Vetenskapsakademiens handlingar", 1745, 6. In recent stiff paper wrappers. Uncut, nice and clean. Pp. 116-17. [Pp. 115-18 present].

Seminal first printing of the first actual description of (speech order) aphasia.

Linné here describes the case of a patient of his, who suffered from gout, which in the fall of 1742 went to his brain instead of his feet. For the first time, we here find an actual description of speech order aphasia, as Linné states "... he seemed to be raving... he was sort of speaking his own language, having his own names for all words... He had forgotten all the nouns, so that he did not remember one single one; not even the name of his children, his wife or himself, let alone anybody else. And what was even more strange, if you mentioned something he wanted to say, he said yes; but if you asked him to repeat it he replied "can nothing", when he saw someone's name, he knew who it was, and when he wanted to mention one of his colleagues, he pointed to the Catalogum Lectionum, where the name was mentioned." Linné's conclusion is: "Thus, he had lost two things; first the memory of all nouns, and second, the ability to name the nouns." [Own translation from Swedish]. This condition lasted till about Christmas, and the following year, the patient died.

The present work is highly interesting in more than one respect. Fist it is of great importance as being the first actual description of speech aphasia, and the first description of aphasia to be given accurately by a physician (vague descriptions of something that might be similar had occurred in blurred forms in the 16th century, and it may therefore be considered not quite accurate, when Garrison and Morton state of the present treatise "Aphasia first described"). The year before Linné's treatise, the great Enlightenment philosopher Biambattista Vico had reported the first known case of a verb production aphasia, and when Linné the following year describes the first reported case of impaired noun production, we actually here, within one year, establish an identification and documentation of both verbal- and noun- dissociation of lexical category retrieval, and thus the actual foundation of aphasia-research.

"Anomia, especially word-finding difficulty affecting nouns and other substantive words, was well documented before epochal observations of Paul Broca ushered in the modern era of aphasiology. A man who lost the "memory of all substantives" as well as the "power to name the substantives" was reported in 1745 by Linnaeus, the Swedish botany taxonomist." (Kirshner, "Handbook of Neurological Speech and Language Disorders, p. 166).

"SPEECH DISORDER Aphasia was described by Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) in 1745 and the site of the lesion in the brain causing it was suggested by Jean Baptiste Boulland in 1825." (Sebastian, "A Dictionary of the History of Medicine").

Apart from those two aspects of the present article, it also raises highly important questions within the fields of psychology, philosophy, linguistics, and logic. Aphasia raises essential questions about the relation between brain and language, a theme which has occupied almost all modern analytical philosophers and logicians (e.g. Wittgenstein etc.), and it thus plays an important role in the area of research of these disciplines.

Garrison and Morton: 4616; Hulth: p. 44.

Order-nr.: 39825